But of course, you couldn’t do that in Japan! Part One

An old post of mine about the thorny issue of how and why teachers may want – or need – to tackle issues surrounding diversity in the classroom was recently quoted in a very interesting post on similar issues, but from a Belgian perspective. In a piece on the excellent BELTA website, Eef Lenaers wrote about the frustration she sometimes experiences when her students come up with gross over-generalisations about other cultures and what can be done about this. Now, all of this got me thinking about an old talk I used to do on the conference circuit ten or so years ago, which tried to address similar issues, and I figured that as I’ve been utterly useless at blogging of late, amidst various madness that’s been visited upon me, it might be a good idea to dig that old talk up and turn it into a post. Better than nothing, eh? So here goes . . .

Frequently after classes, my students will come up to me and ask “But where are you from? You’re not very English!” Over the years, I’ve learned to delude myself into taking this as a compliment: it must be down to my warm, out-going personality, I assure myself; or perhaps it’s the fact I’m not that bad with languages, that I’m chatty, and possessed of a lust for life. These moments help me stave off the sad fact that really I’m scruffy, prone to mumbles and rants, and somehow inherently shabby in the way that only those reared on bacon sandwiches and milky tea can ever truly be!

At home, however, it’s often a totally different story. I have a non-British partner, and the last line of attack, the riposte to which there is no return, is always “God! You’re so bloody ENGLISH!” This can mean anything from you’re the kind of sad, repressed person who walks out of the room to break wind to why on earth can’t you phone someone just because it’s after 10 in the evening! It could be quiet rage at my not wanting to talk about sex – or even really talk at all very much full stop, or else anger at my refusal to ever admit to feeling down or pissed off when the brown stuff starts hitting the ventilation. Whatever, it still comes as really quite confusing. I am English by birth and by upbringing. I feel intensely connected to certain aspects of life in Britain, repelled and appalled by others. And yet in the eyes of the outside observer, I seem to flit back and forth across a line of some supposed cultural finality.

The first point to make here is that both national identity and the notion of culture that it is so frequently associated with are far more complex than the simple retorts above suggest. However, it still tends to be the trite and the simplistic which prevails within EFL. Culture in English Language Teaching materials is a simple black and white affair; or rather, it is all too often simply white: antiseptic, anodyne, bleached and sanitised and bland. As a teacher trainer, this becomes most apparent when watching trainees use widespread EFL materials. Trainees generally come to the classroom with little or no experience and thus view the coursebook as an expert source of knowledge and as somehow implicitly right. The notion of culture as propagated in coursebooks tends to either revolve around the presentation of literature as a vehicle for culture, so the old Headway Pre-Intermediate, which I once used on a CELTA course, had, for instance, an extract from Dickens which includes such choice lines as “The mild Mr. Chillip sidled into the parlour and said to my aunt in the meekest manner ‘Well, ma’am, I’m happy to congratulate you’”. The many hours of fun to be had by watching trainees on their second teaching practice slot trying to explain to bemused students what a parlour is or how exactly you sidle is tempered only by an awareness that this is singularly useless vocabulary for learners of this level to be learning!

Another angle on the culture issue crops up in a text in an Upper-intermediate book called ‘Soho: My favourite Place”. I’m not sure how many of you are familiar with the wonderful mess that is Soho, but the last time I looked, it was still as full of drug dealers, gay bars, meat-head bouncers policing dubious late-night binge-drinking establishments, transvestites and menacing-looking characters lurking in shadows as it has ever been. Not in Headway, though, of course! Oh no! The nearest any of this comes to impinging on the antiseptic world of the coursebook is the admission that “the place is a bit of a mess”, whilst readers are coyly told that there are “surprises around every corner”. Those of you familiar with a bit of classical mythology may also be surprised to learn that Eros apparently celebrates “the freedom and friendship of youth”! This is culture as a kind of white-washed national tourist board ad.

All of this is then compounded by a persistent triteness which reduces people from other countries down to their crudest stereotypes, as in yet another text from a well-known coursebook that looks at ‘Minding your Manners Around The World’. Here, trainees get to inform students that if they are expecting the arrival of foreign business colleagues, they can be sure that Germans will be bang on time, Americans will probably be fifteen minutes early, Brits will be fifteen minutes late and as for the Italians! Well, you’d best allow them anything up to an hour! The supposed veracity of these gross, offensive stereotypes is not even challenged by the methodology. The kinds of questions students are asked to discuss after reading the text are almost always simply comprehension-based, so they are forced into uncovering ‘Which nationalities are the most and least punctual’, for example.

It seems to me that three broad issues arise from all this: the basic question of what exactly culture is, how trainees can be made more aware of it, and how a broader notion of culture leads to methodological changes. I strongly believe that even initial preparatory courses such as CELTA should be addressing these sensitive areas. Here, though, I’ll just try to outline some basic notions of what culture might actually involve – and look briefly at how this could impact on initial training.

The title of this particular post comes from a comment made to me early on in my teaching career. It was, presumably, intended as useful guidance to a rookie teacher and also perhaps as some strange form of protection for any mono-cultural Japanese classes that might later be encountered. The myth of the difference and uniqueness of the mono-lingual, mono-cultural context is a very damaging one in that it insists on speakers of one foreign language somehow all being equal participants in a shared, mutually agreed upon culture. Those still clinging on to such an idea might like to discuss the following exercise (later adapted for OUTCOMES Advanced) which we frequently used to do with CELTA trainees on our courses.

GOD SAVE THE QUEEN?

1. Are the following part of British culture? In what way?

2. Do any of them mean anything to you personally? What?

3. Have you seen any of them mentioned in EFL materials? In what capacity?

God Save the Queen

bacon and eggs

Balti curries

lager

port

the Costa del Sol

a week in Provence

ballet

the Proms

Reggae

Old Labour

Conceptual Art

The Beautiful Game

The Environment

bowler hats

Notting Hill

French art-house films

Irvine Welsh

Cockney rhyming slang

Shakespeare

Islam

Sunday school

marijuana

Cricket

Direct Action

Harrods

car boot sales

St. Patrick’s Day

kebab shops

Easter

Chinese New Year

ackee and salt fish

My own take on this is that all of the above form part of the complex fabric of modern British life in one way or another and that the degree to which each is relevant to any individual with any connection to British culture depends on the webs of micro-cultures we each weave for ourselves. As such, there is very clearly no such thing as ‘British culture’ in any monolithic sense – it is rather, as the axiom has it, horses for courses, and the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. You also cannot make assumptions that, say, reggae and marijuana will always overlap or that Islam should somehow exclude fish and chips! It should also be added that not only will the same intense involvement in a wide variety of micro-cultures be the case for all foreign learners, but that often – as moneyed, globally-oriented beings – many of our students will frequently participate enthusiastically in exactly the same globalised micro-cultures as many native-speakers. This is where non-native speaker teachers, working in the countries of their origin, have a huge advantage over native-speaker teacher imports. The local teachers will almost always know far more about the macro-culture of the country they are teaching in and can thus use all of this knowledge to hook new language onto in ways that are pertinent and meaningful to their students. Once you accept that mono-lingual certainly does NOT mean mono-cultural, at least when one is thinking of culture in terms of micro-cultures, then the gap that then remains can be envisaged less as cultural and far more helpfully as a purely linguistic one, with any attitudinal differences that each participant in any micro-cultural discourse might feel then being acknowledged and negotiated through language. Such an understanding of the way we all contain and negotiate a vast variety of cultures within our day-to-day lives will hopefully result in the end of essentialising comments about what ‘Arab’ or ‘Muslim’ or ‘Chinese’ or ‘Turkish’ students can and can’t somehow cope with in classes, and will lead instead to a classroom culture in which students in ANY context are given the time, space and language to be first and foremost their own complex selves.

I’ll leave it there for now, but be warned: there’s a part two to all of this and maybe even a part three waiting in the wings.

I’ll see what comes back in response to this one first and take it from there.

Ways of exploiting lexical self-study material in the classroom part two: some things we can get students to do

In the first part of this post, I explored some of the things that you can do as teacher – both in terms of preparation / planning and in terms of actual classroom practice – to help to take lexical self-study material off the page and to bring it to life and make it more real for the students. In this post, I’m going to assume that that message has already been absorbed and am going to move on to talk about what you might do next. Once you’ve given students time to go through an exercise, you’ve out them in pairs to check their answers, you’ve elicited answers from the whole class and, as you did so, you’ve explored the language in the sentences and expanded upon both the items there and connected bits and pieces. You have a board full of great, connected, whole-sentence fully grammaticalised input . . . and then what?

In case you’ve forgotten – or never read the first post to begin with – here again is the exercise I’m describing, and thinking about how to exploit:

Well, the most obvious thing is to get students talking about their own ideas, experiences and opinions using the language they’ve just looked at. The way I’d usually do it is to prepare some questions based on what’s there. Take, for instance, the first item – address an issue. You could just ask What are the main issues in your country? Do you think the government is doing enough to address them? Those aren’t bad questions, but to support students more, and give them more ideas of what to talk abut, I’d probably twist this slightly to something like this:

Decide which three of the issues below are the biggest problems in your country.

Mark them from 1 (=most serious problem) to 3.

Alcoholism

Domestic violence

Drug abuse

Unemployment

Illegal immigration

Non-payment of taxes

A growing wealth gap

Digital connectivity

Illiteracy

Public and private debt

Now tell a partner which three issues you chose.

Explain why you think they are such big issues, what is being done to address them – and anything else you think could be done to improve the situation.

Just this on its own would be quite sufficient for a good fifteen-minute speaking slot in class. I’d give students a few minutes to read through and to ask about any vocabulary they weren’t sure of – there’s bound to be some in the list above. I might then model the task by explaining which of the above I think is the biggest issue in the UK (they’re all contenders, if truth be told, but personally I’d opt for the growing wealth gap!), why and what’s being done about it. Once I’d stopped foaming at the mouth about the fact my prime minister is currently at an EU meeting to lobby for the right to ignore Europe-wide restrictions on bankers’ pay whilst more and more of the people he’s supposed to be looking after are increasingly reliant on food banks, I’d then put students in small groups of two and three and get them to discuss their own ideas.

As students talk, I’d go round, listen in, correct any pronunciation errors I might hear, ask questions and chip in with the discussion and – most crucially – try to find things students were trying to say, but couldn’t quite . . . or things they were saying that I would say in a slightly different (and better!) way. I’d zap backwards and forwards to the board and write up whole sentences, with the odd word here and there gapped. Once things were slowing down and some pairs / groups had almost finished, I’d stop the whole class and say OK, that was great. let’s just quickly look at how to say what you were trying to say better. I might have something like the following on the board:

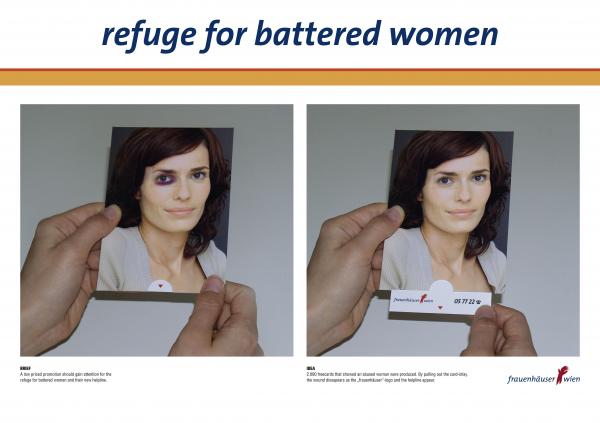

A lot of men are frustrated with their l………… in life and then drink and end up t……………… it out on their wives. A lot of women f…………….. their homes and end up in r……………… for battered wives. Unemployment has r………………… over the last couple of years. Loads of people are moving abroad in s………… of work. We’re being f…………….. / s…………… with immigrants. It’s causing serious f………………. in lots of areas.To elicit the missing words, I’d basically paraphrase / retell the things I’d heard by saying things like this: A lot of people are unhappy with where they are in life they’re unhappy with their position, with what they’ve achieved, so they’re unhappy with their MMM in life. Anyone? No? They’re unhappy with their lot in life. And they drink and get angry and come home frustrated and they’re angry at the world, but they hurt their wives instead. They feel angry and frustrated, but don\’t know what to do with that anger, so they MMM it out on the ones they love. Yeah, right. They TAKE it out on them. And as a result, some women escape from the family home, like people MMM a disaster or MMM a war. Anyone? Yes, good. They FLEE and they end up in special buildings where women who have been beaten up – battered women – can hide and be safe from danger. These places are called? No, not refugees. Refugees are people who have to flee their own countries. The places are called REFUGES. Where’s the stress? yeah, REFuge, but ReFUgee. Good.

Other questions connected to the vocabulary in the exercise that I might ask students to discuss could include the following:

- Can you think of a time when law and order completely broke down in your country? What sparked it? How long did it last?

- Why do you think some people might not agree with aid agencies providing emergency relief? What do YOU think about it?

- Can you remember any news stories from the last few months about an area needing emergency relief? Why? What happened?

- Can you think of anyone who’s been arrested for inciting violence or racial hatred? What happened?

- Would you like to be a social worker? Why? / Why not?

With any of these, again I’d give them a minute or two to read through and ask questions about. I’d model and I’d then listen in and find things to rework, before ending up by reformulating student output on the board. If you’re not sure of your ability to hear things in the moment and to think of better ways of saying things, you can always cheat by doing exactly what I did above and plan in advance things you think students MIGHT or COULD say, decide the best words to gap, and then simply write these up whilst monitoring. You can begin by saying OK, here are some things I heard some of you saying. Fools them every time!

In the third and final post in this little series, I’ll outline some other things you could get students to do with an exercise like this.

Cheers for now.

Hugh

What have corpora ever done for us?

Following a conversation over on the facebook page I use for talking about teaching and language, I’ve decided to post a talk I did at IATEFL many moons ago. I do remember, with a faint smile, that Dave Wills himself came along to watch this one, but at some point became overcome with either rage or tedium and flounced out, thus allowing me to make the cheap jibe about Elvis having left the building before carrying on. Were this post to generate even a tenth of that heady level of excitement, I’d be delighted!

Written maybe ten years ago, at the height of the corpora promo boom, it was intended as a partially tongue-in-cheek critical overview of corpora linguistics. And yes, for those of you that were wondering, the title WAS inspired by this rather splendid Monty Python sketch:

With that in place, here goes nothing . . .

The use of computers to store and help analyse language has obviously revolutionised many aspects of language teaching, and corpora linguists have become an ever-present feature at IATEFL and other similar conferences. Obviously, much good has come from this. We have had a whole new generation of much-improved dictionaries, all of which contain better information about usage, collocation and frequency; superb new reference books such as the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English have been made possible, and, perhaps inadvertently, corpora linguistics helped to launch the Lexical Approach and to thus help to move language at least some way back towards the centre of language teaching. Nevertheless, it seems to me that despite all these advances, corpora linguistics has also had several negative side-effects on the way teachers perceive their roles, and that they have actually enslaved us in ways which are not entirely healthy. I would like to move on to consider the ways in which I feel this has occurred.

The fallacy of frequency

Corpora linguists repeatedly promote their products with often highly-detailed reference to frequency counts and the idea that frequency is central has become a common one. However, should a Pre-Intermediate learner wish to be passed the salt over dinner, simply knowing the infrequent item ‘Salt’ will facilitate this in a way that knowing the far more frequent ‘Could’, ‘you’, ‘pass’, ‘the’ and ‘please’ would not. Generally, it’s not the most common words which carry core meanings; rather, it’s the far rarer items that do. Simply knowing the 800 most common words in the language makes you only able to say a lot about not very much. In the same way, failure to learn word which may well be low-frequency generally, but which are possibly much higher frequency within specific types of conversations condemns you to not being able to say very much about a lot!! Frequency tells us nothing more than what is frequent. It cannot tell us what’s useful, what’s necessary or even what’s teachable.

There are deeper problems here to do with the way in which frequency is actually calculated. Corpora remains word-obsessed and the process of lemmatisation compounds this. Hence, an idiom like ‘You’re a dark horse’ is entered not as a two-word idiom, but rather as one example of ‘dark’ and another of ‘horse, thus defaulting on two fronts. Similarly, plural nouns are currently counted as other examples of singular ones, which is a rather major oversight. Is, for instance, the singular of ‘Many Happy Returns’ ‘A Happy Return’? ‘Meetings’ is not simply the plural of ‘meeting’, and it collocates with different words. Finally, knowing that, say, ‘get’ is a very common word does little to help teachers know whether ‘get on with it’ is more frequent that’ Let’s get down to business’. Sadly, until corpora start sorting by chunk they will remain of limited relevance.

The fallibility of human endeavour.

That corpora need to be approached cautiously and with one’s intuition fully tuned is made apparent by a cursory glance at the word ‘thaw’ on several published CDs. Should one access the word, wishing to know whether snow melts or thaws, one would be surprised to learn that a far more frequent example of the word, and thus – if we follow the logic of corpora linguists – a more useful collocate for our students is actually John, as in John Thaw, the late, great British actor.

Similarly, I once saw a Jane Willis talk wherein she suggested that one of the most common three-word lexical items in the English language was ‘Princess of Wales’. It was only when pushed during questioning that she actually admitted that the corpora she had taken this data from was based almost exclusively on a couple of radio phone-in programmes. In the same, way, the actual construction of corpora-based materials – dictionaries and the like – also inevitably involve a degree of hammering out by researchers, often by means of a vote or a fudge. Corpora are by necessity human constructs based on limited samples of data, are easily skewed by input and thus are best viewed sceptically.

The limitations of what corpora can offer

While spoken language, conversation, may well form the basis – even the majority – of many corpora, what corpora can’t show us is what typical conversations look like. It’s not possible, for instance, to access ten typical conversations had by people talking about what they did last night or to look at the 20 most common ways of answering the question “So what do you do for a living, then?”. As such, if we want to present our students with models of the kinds of conversations they themselves might actually want to have, we are forced to fall back on our (actually ample) experience of such conversations in order to script them. However, I would argue that it is precisely because we have got such broad experience of such conversations that we do tend to know how they work and sound and look.

For teaching purposes. we need to be able to script conversations that aren’t so culturally and spatially bound as to exclude students; we need to ensure the conversations students are exposed to still somehow facilitate intra-class bonding. Input needs to be proto-typical and to include items which are easy for us to systematise and for learners to appropriate and assimilate. Corpora cannot do this for us.

Corpora and the non-native speaker teacher

It is often claimed – mainly by those who are employed to make, package and sell corpora – that corpora are an invaluable aid for the non-native speaker teacher. I would personally argue that the opposite is far too often true and that as they stand, corpora massively favour native speakers.

One understandable reaction many teachers, both native and non-native, have to the notion that they should teach more spoken English is the ‘but I’d never say this or that bit of language” response when faced with a spoken text. Ironically, written texts never elicit a similar “But I’d never write that myself” response, and there are several reasons for this, I feel. There is possibly an assumption that writing is a more creative realm where anything goes; there’s also the fact that the grammar and the lexis of the written language have already been codified and disseminated and are thus more familiar to teachers; thirdly, I think, there’s the fact that we pin our identities on our speech – our idiolect, our regional, class-based, age-oriented, in-group, gender-based grasp of lexis and grammar – far more profoundly than we do on what we write. We are so aware of differences in the way we speak that we usually fail to notice the massive similarities. A good example of this is the fact that every EFL book which focuses on the UK / US divide fails to note that the vast majority of the language used in both countries is remarkably similar, and instead frets over the present perfect, sidewalks versus pavements and the correct pronunciation of aluminium. Yet for every “It can out of the blue” / “It came out of left-field’ divergence, there must surely be ten other idioms we all have in common.

Given this, I personally feel it doesn’t take much to persuade non-native speaker teachers to stick to the already familiar, tried-and-tested formula of written texts and comprehension questions and structural grammar. By spending so much time pointing out relatively obscure quirks and neologisms, such as the fact that ‘like’ is being increasingly used to report speech (as in “He was like ‘Hi’ so I was like ‘Bye’) , corpora linguists are inadvertently making spoken English more of a foreign language for non-native speaker teachers than is perhaps wise for people who claim to believe – as I do – that spoken English should become much more a part of General English than is currently the case. Too relentless a focus on the new, the odd, the interesting, the different obscures the wealth of English that unites us all.

I also feel that it is not only many non-native speaker teachers who would never use ‘like’ in this way, but also many native speakers too. The vast majority of language teachers do NOT need corpora to tell us that this is a relatively unuseful piece of lexis, so long as it remains still relatively unused. Indeed, my own rule of thumb would be that if YOU don’t say it, don’t TEACH it. English as a foreign language is NOT English as the corpora knows it. If you believe, as I do, that the kind of model conversations coursebooks provide for teaching purposes should be better modelled on the information provided by corpora than is currently the case, then I find it hard to see how you couldn’t also support the idea that corpora specialists should concentrate more on insights which will be of direct use to coursebook writers and teachers alike. Indeed, given the problematic status of spoken language within the classroom at present, I’d go so far as to say assert that failure to do anything less serves to sabotage attempts to spread a methodology based on spoken language (and here, of course, I’m compelled to acknowledge my own interest in this area as a coursebook writer).

I find it particularly interesting to note that the constructors of corpora – or at least their backers – seem as yet very reluctant to work on a corpus of English as used by non-native speakers. Obviously, this would be in essence the same corpus, but with much left out. This is precisely the point : that which is left out by competent non-native speakers has no real place in most – and especially most pre-Advanced – teaching materials.

Animal Farm (or Beware of the oppressive tendencies of those who come claiming to liberate us!!)

It would be churlish to deny that corpora have provided us with some useful insights into such features of language as the fact that would is three times more common when talking about past habits than used to is, but at the same time it must also be added that the way in which corpora have been presented has all-too often intimidated us into pretending that we didn’t already know much – if not most – of what they confirm. For example, Mike McCarthy, at IATEFL Brighton 2001 spent half an hour blinding us with the statistics that showed – entirely unsurprisingly – that ‘take the mickey’ is far more common than ‘mickey-taker’ or ‘mickey-taking’. Surely any fluent speaker of the language could have guessed this (dubiously relevant) fact themselves, based on their own intuitions about the language.

The relentless emphasis on the finality of corporal truth no only denies the reality of the classroom practitioner who has to get in there each and every day and try to give their students information about the language being studied, but also refuses to acknowledge the fact that we all have heard and read millions and millions more words than any corpus will ever hold and thus have good hunches about words as a result. Sure, hunches about language can be wrong, but more often than not, they aren’t. I personally really resent the notion that not only are corpora useful for showing us the errors of our ways, but also for confirming when we’re right. The implication is that we are not right UNTIL we’ve checked! This way lies madness – and the deskilling of us all!!

Conclusions

Obviously, it is important that teachers do keep themselves up-to-date with corpora findings and adapt their understanding of the way language works accordingly. Here I totally agree with Ron Carter that one thing corpora has helped us become more aware of is the fact that grammar is much broader than sentence-based / tense-based grammar would seem to suggest. Words have their own micro-grammar and so lexis needs to continuously be grammaticalised in typical ways. Nevertheless, it is also vital that teachers are encouraged to believe that they can tap into and trust their own inner corpora.

If Carter and McCarthy can proclaim that the more students are encouraged and trained to notice, the more they actually will notice, then the same much surely be true for us as teachers. Indeed, the true sign of corpora-work well done is its own eventual redundancy. This really brings me to my final point – one of the great ironies of corpora is that they have actually unwittingly made teachers more intuitive, not less. What corpora have done is to place language back at the centre of classrooms and, as such, we all now have to think much more about how we actually use language.

To a degree, corpora and teachers exist in a parent-child relationship, and many teachers are now ready to leave home. Thanks Mum and Dad – you’ve done a great job, we may be back to visit every now and then, but we’ve basically already got the message!

However, lest we forget, corpora are bank-rolled by major publishing houses and have endless spin-off publications derived from them in an effort to recoup much of this investment. As such, maybe I’m expecting too much by asking those in receipt of the publisher’s pound to loose the reins on much of their power and place it back where it rightly belongs – back in the hands of the humble classroom practitioners!!!